The Slow Burn of Reacting: On Digital Outrage & The Architecture of Response

Share

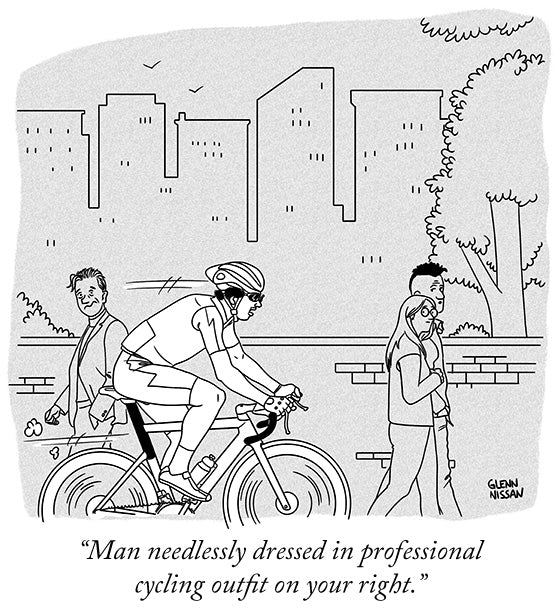

A cartoon from The New Yorker appeared in my social media feed yesterday morning, arriving with the casual inevitability of digital serendipity. The caption read something like: “Man, needlessly dressed in a professional cycling outfit on your right.” The drawing itself possessed that particular New Yorker quality—dry, observational, quietly absurd in the way that good humor often is, capturing one of those minor social phenomena that we all recognize but rarely articulate. Three pedestrians walked along a sidewalk while a cyclist passed by in his aerodynamic outfit, perhaps more suited to the Tour de France than a casual neighborhood ride. I found myself chuckling at the gentle truth of the observation. The way it illuminated something simultaneously trivial and somehow universal about contemporary urban life.

Then I made the mistake of reading the comments.

The first response that caught my attention declared with unmistakable irritation: “I’m recalling a period when cartoons were aimed at humor.” Hundreds of replies followed in that peculiar cascade of digital discourse: some amused, others genuinely offended by the perceived slight against cycling enthusiasts, many offering earnest explanations about the practical benefits of proper cycling attire. My initial reaction fell into a familiar groove of contemporary cultural criticism: people take things too seriously these days, I thought, as if I were the first person to make this observation.

However, a counterpoint emerged in my thinking: perhaps humor itself has drifted steadily toward offense, become more pointed, more targeted, less generous in its spirit. And then something else occurred to me, something that felt closer to the actual heart of the matter: our fundamental reactions to humor, to perceived slights, to the minor irritations and pleasures of daily existence haven’t changed at all. What has transformed completely is how we respond to the responses of others. And the unprecedented fact that we’re now privy to every stranger’s immediate emotional reaction to virtually everything.

Social media granted everyone not just a voice, but a platform, and an audience, and with them, an opinion about every piece of content that crosses their digital path. I still struggle to understand why so many of us feel compelled to comment on everything we encounter online, particularly when the commentary amounts to nothing more substantive than public disagreement. I imagine that first commenter in an earlier era, sitting at his kitchen table with morning coffee, flipping through the actual magazine. He might have grimaced at the cartoon, perhaps muttered something under his breath about the decline of sophisticated humor, burned his tongue slightly on his coffee while contemplating the thought, and then moved on with his day, the minor irritation dissolving into the larger stream of daily experience.

Now, instead, he’ll think about that cartoon intermittently throughout the day. Notifications will arrive like digital breadcrumbs, leading him back to check whether anyone has responded to his comment, whether others share his perspective, and whether he needs to defend or clarify his position. The reaction becomes a self-sustaining loop of attention and resentment, creating what researchers describe as “reduced productivity, heightened anxiety, and spiraling depression” as we become trapped in cycles of digital engagement.

We do possess a choice not to share every passing thought with the world; however, most people seem to have lost touch with how to exercise that choice meaningfully. We’re neurologically wired for expression; it’s a fundamental aspect of human social behavior. However, we often fail to recognize the nature or consequences of our digital expression until someone responds, unless we’ve deliberately cultivated the kind of self-awareness and impulse control that allows us to pause between feeling and reacting. If most of us consistently exercised such restraint, though, what would become the fundamental business model of Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter? These platforms depend on our compulsive need to respond, to engage, to react.

We express contempt because we can, and because technology makes it effortless and consequence-free. And somewhere in the overwhelming blur of mass digital socialization, we seem to forget that we’re equally capable of expressing amusement, curiosity, grace, or simply saying nothing at all. The medium shapes not just what we say, but how we think about what’s worth saying.

What would happen if, instead of posting every opinion about what isn’t funny, what doesn’t meet our standards, what fails to align with our particular worldview, we merely grimaced quietly, swallowed our digital pride, allowed the minor irritation to burn briefly like coffee on the tongue, and then forgot about it? What if we trained our attention toward what is funny, thoughtful, or genuinely worth lingering over? What if we approached online discourse as an opportunity to amplify what we value rather than constantly critique what we don’t?

The psychological truth remains that you cannot change someone by demanding they accept that their perspective is fundamentally wrong, their sense of humor misguided, their opinions invalid. Such approaches only make people feel diminished, defensive, and more entrenched in their original position. But you can change how you respond, whether to a cartoon about cycling outfits, a political affiliation that differs from your own, or a comedian whose humor strikes you as problematic.

Social media has shaped our collective psychology in ways we’re only beginning to understand. We remain in our cultural infancy regarding these technologies, still learning how they alter not just communication but consciousness itself. These platforms highlight our differences with algorithmic fidelity, amplifying our worst instincts while suppressing our capacity for nuanced thought, and encourage us to represent not our best selves but rather the most reactive and immediately satisfying versions of ourselves. Research consistently demonstrates “a strong link between heavy social media use and an increased risk for depression, anxiety, loneliness, self-harm, and even suicidal thoughts.”

We’re all performing some version of the smartest parts of ourselves while simultaneously displaying some of the least considered aspects of our emotional lives. And the pace of it all demands that we slow down, step back, create space between impulse and expression.

Throughout history, when cultures have cultivated their finest achievements in art, architecture, education, and social organization, it has been because they were focused primarily inward, on refinement, on the patient development of excellence within their own communities. The focus was on becoming rather than critiquing, on creation rather than reaction, on understanding the complexity of their own traditions rather than constantly monitoring and judging the perceived shortcomings of others.

Everything moves too quickly now. When we exist in states of chronic anxiety and digital overstimulation, our neural systems struggle to distinguish between genuine threats and manufactured urgency, between actual problems and those we create through our own reactive patterns. As psychology research shows, “discomfort is a powerful motivator, so the mind gets to work focusing on the ‘problem,’” often creating “mental loops” of rumination and reaction. We manifest the very problems we think we’re identifying and resolving. It becomes the shadow side of positive thinking; instead of visualizing what we want, we obsessively focus on what we fear or resent, thereby creating more of it.

So perhaps—and this is merely a suggestion, not a prescription—we might consider the metaphorical equivalent of not needlessly dressing in professional cycling outfits for casual rides through our neighborhoods. Perhaps we can make it easier on ourselves to slow down, to respond rather than react, to choose our battles more carefully, to remember that not every passing thought requires public expression. Perhaps we can rediscover the lost art of letting minor irritations dissolve naturally, without amplification, without the addictive feedback loops of digital engagement.

The cartoon was, after all, just a gentle observation about the small absurdities of contemporary life. In a healthier cultural moment, it might have elicited a chuckle, a moment of recognition, maybe a brief conversation with someone sitting nearby. Instead, it became another battleground in the endless war of perspectives that characterizes so much of our online existence. The professional cycling outfit, in the end, might be the least of our problems.